For twenty-six years, Nigeria has clung to the promise of the "Fourth Republic," a Western-style liberal democracy that many hoped would bring prosperity, security, and the rule of law. However, as we stand at the tail end of 2025, that promise feels further away than ever. To the average citizen, the "dividends of democracy" have been replaced by the "debts of dysfunction." It is time to speak the uncomfortable truth: democracy, in its current Nigerian iteration, has failed, and the nation is in desperate need of a radical reset.

The primary duty of any government is the protection of lives and property. On this front, the failure is absolute. From the resurgence of mass school kidnappings in the North to the unchecked banditry in the Middle Belt, the Nigerian state has lost its monopoly on violence.

The security breakdown is no longer a localized issue; it is a national crisis. When children are snatched from schools and farmers are slaughtered in their fields, the "social contract" is effectively nullified. The current administration’s inability to secure the nation suggests that the civilian command structure is either too compromised or too weak to confront the warlords and terrorists who now operate as shadow governments.

2. Mass Looting and Economic DespairIn 2024 and 2025, Nigeria witnessed a phenomenon that shook the nation: the desperate, hunger-driven looting of food warehouses and grain trucks.1 This was not mere criminality; it was a symptom of a systemic economic collapse. While the political elite live in luxury—purchasing multi-billion Naira presidential jets and renovating luxury mansions—the masses are literally starving. The "looting" by the people is merely a mirror of the "mass looting" of the national treasury by a political class that treats public funds like a private inheritance. Inflation, fuel price hikes, and a plummeting currency have turned Nigeria into a pressure cooker waiting to explode.

3. A Judiciary in ChainsThe judiciary is supposed to be the "last hope of the common man."2 Instead, it has become a marketplace where justice is auctioned to the highest bidder. The perception of the judiciary as corrupt and partisan has reached an all-time high.Cases of high-profile corruption are languishing for decades, while "technicalities" are used to shield the powerful from accountability. When the people no longer believe they can find justice in a courtroom, they will eventually seek it in the streets. A democracy without a functioning, impartial judiciary is nothing more than a legalized kleptocracy.

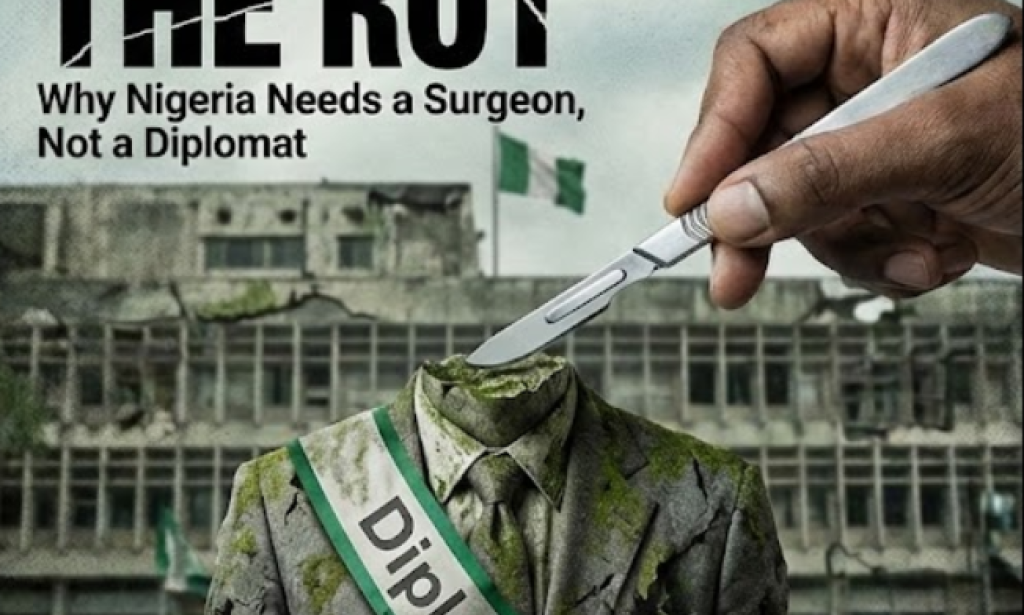

4. The Case for a Radical AlternativeThe failures are so deep-seated that incremental reform feels like applying a bandage to a severed limb. This has led to two radical proposals currently dominating public discourse:

-

A Temporary Military Reset: Proponents argue that only a disciplined, "strongman" military rule can break the back of insecurity and clear the corrupt political landscape. Historically, military rule has its own scars, but some argue that a "corrective regime" is necessary to purge the system before any future return to civilian rule.

-

Modified / Indigenous Democracy: Others argue for a "Nigerianized" democracy. This would move away from the expensive, corruption-prone American presidential system toward a model that integrates traditional leadership, meritocratic councils, and a parliamentary system that is cheaper to run and more accountable to the grassroots.

| Current System (Failed) | Proposed "Modified Democracy" | Military Rule (The "Corrective" Option) |

| Leadership: Career politicians driven by patronage. | Leadership: Merit-based councils and traditional leaders. | Leadership: Centralized military command. |

| Security: Fragmented, underfunded, and reactive. | Security: State-led with decentralized community policing. | Security: Martial law and aggressive enforcement. |

| Cost: Massive overhead; billions spent on elections. | Cost: Low-cost, non-partisan administrative model. | Cost: Minimal; focus on operational efficiency. |

| Outcome: Systemic corruption and poverty. | Outcome: Stability and indigenous accountability. | Outcome: Rapid "cleansing" but high risk of autocracy. |

While the Western "liberal democracy" model is often presented as the gold standard, several developing nations have achieved stability, security, and economic growth by adopting "modified" or homegrown systems. These precedents offer potential blueprints for what a "reset" in Nigeria might look like.

Here are four historical and contemporary models of "modified democracy" that have successfully addressed the issues of corruption, security breakdown, and lawlessness in developing contexts:

5. The Technocratic Centralism Model (Rwanda)Following the 1994 genocide, Rwanda transitioned into a system that prioritizes national cohesion and developmental outcomes over multi-party competition.

-

The "Consensus" Pillar: Rather than "winner-takes-all" politics, all registered parties participate in a National Consultative Forum to build a minimum national agenda.

-

Accountability via Imihigo: Nigeria’s issue with "mass looting" and "failed projects" is addressed in Rwanda through Imihigo—performance contracts. Every official, from ministers to mayors, signs a public pledge of what they will achieve. If targets aren't met, they are removed.

-

Application for Nigeria: This model suggests that security and development can be achieved by centralizing authority around a strict, performance-based technocracy that punishes corruption with military-like precision.

Under Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore transformed from a "primal swamp" into a global power by adopting an "illiberal democracy."

-

Meritocracy over Patronage: Singapore effectively eradicated corruption by paying public officials very high salaries (to remove the incentive for bribery) but enforcing draconian punishments for those who still stole.

-

Restricted Dissent for Stability: The state prioritizes "existential survival." Political competition is permitted but heavily regulated to prevent the kind of ethnic and religious polarization that often paralyzes Nigerian governance.

-

Application for Nigeria: Nigeria could adopt a "Meritocratic Council" where key sectors (Security, Finance, Judiciary) are led by proven experts who are insulated from electoral politics, focusing on long-term stability rather than the next election cycle.

Botswana is often cited as Africa’s most stable democracy because it didn't just copy the West; it anchored its parliament in the Kgotla system.

-

Integration of Traditional Authority: The Kgotla is a traditional village assembly where any citizen can challenge a leader. By integrating these indigenous structures into the modern state, the government maintains a level of "grassroots legitimacy" that Western systems lack.

-

Customary Justice: In Botswana, traditional leaders handle 80–90% of judicial cases. This relieves the "corrupt judiciary" bottleneck by providing fast, cheap, and culturally understood justice at the local level.

-

Application for Nigeria: A modified Nigerian democracy could officially empower the House of Chiefs or traditional rulers with specific judicial and security roles, using their local influence to stop banditry and resolve disputes where the formal police have failed.

Several nations have used a "military-civilian dyarchy" to transition out of total state collapse.

-

The "Corrective" Pause: In some cases, a disciplined military intervention is used not to stay in power forever, but to "purge" the political class and rewrite the constitution (as seen in some historical South American and Asian "Tiger" economies).

-

Modified Voting: This might involve "non-partisan" elections where candidates run on their personal merit and professional records rather than under the banner of giant, corrupt party machineries.

If Nigeria were to move toward a Modified Democracy, it might look like a combination of these elements:

-

Performance Contracts (Imihigo): Making the budget transparent and holding every governor personally and legally liable for specific security and infrastructure targets.

-

The Kgotla Judiciary: Decentralizing the "corrupt judiciary" by giving traditional and community courts the power to handle civil and minor criminal cases, reducing the backlog and the opportunity for high-level bribery.

-

Technocratic Vetting: Requiring that certain ministerial positions (Defense, Finance, Justice) be filled from a pool of non-partisan experts vetted by a "Council of State" rather than political appointees.

-

Security Decentralization: Using a "guided" military approach to train and oversee state-led community militias, moving away from the failed centralized policing model.

Nigeria cannot survive another decade of this "hollow democracy." The present administration is riddle with the same ghosts of the past—corruption, mass looting, and a total breakdown of the rule of law. Whether the answer lies in a firm military intervention to stabilize the sinking ship or a completely modified democratic structure that reflects our unique cultural realities, one thing is certain: the current status quo is a death sentence for the nation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.